A few remarks on French Theory

Robert Steuckers

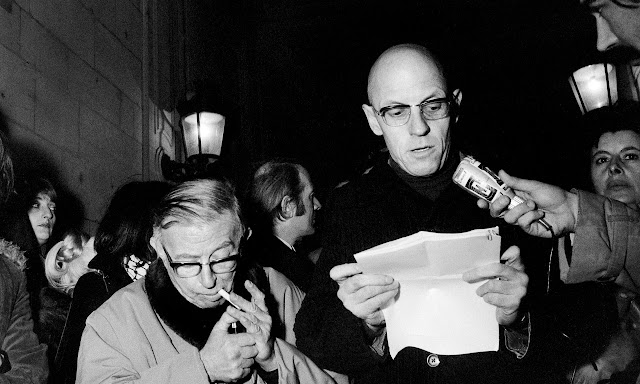

I am often asked where I stand on what the American academic world calls 'French Theory'. It may seem ambiguous. In any case, it does not correspond to the position adopted by the personalities whom the labelling maniacs unwillingly place at my side. François Bousquet, a neo-right-wing or rather neo-neo-right-wing theorist, recently wrote a pamphlet against the contemporary ideological effects of the ideology that Michel Foucault sought to promote through his many happenings and farces that challenged the established order, through his openness to all kinds of marginality, especially the most outlandish. On the face of it, neo-right-wing comrade Bousquet, who has hooked his wagon to the 'historic canal' of this movement, is quite right to castigate this Parisian carnival, now three or four decades old (*). Festivism, masterfully criticised by Philippe Muray before his sadly premature death, is a fundamentally anti-political device that obliterates the proper functioning of any city, handicapping its optimal deployment on the world stage: in this absurd context, there has never been so much talk of "citizenship", whereas festivism destroys the very notion of "civis" of Roman memory. Since Sarközy, and even more so since the start of Hollande's five-year term, France has been paralysed by various deleterious forces, of which the more or less buffoonish avatars of this post-Foucauldian festivism play a large part.

The French intellectual landscape is invaded by this unfertile luxuriance, which spills over, via media relays, into the daily lives of every 'citizen', distracted from his or her nature as a zoon politikon in favour of devastating histrionics. Bousquet's anti-Foucauldian interpretation may therefore be legitimate when we diagnose a France gangrened by various pernicious forces, including the festivism inaugurated by the Foucauldians before and after the death of their guru.

However, another approach is perfectly possible. The West, which I have always defined as a negative ideological and political entity and a vector of decline, is made up of a dense complex of control devices installed by unhealthy powers claiming to be Descartes and above all Locke. Today, these Cartesian/Lockean devices, Western in the negative sense of the term (especially for Russian thinkers), are being criticised by a current figure on the American left, Matthew B. Crawford. Crawford was originally an academic philosopher who rejected these abstruse and derealistic ideological-philosophical devices to become the entrepreneur of a fine motorbike repair shop. He explains his choice: it was an in-depth reading of Heidegger that led him to the definitive rejection of this Western philosophical-political apparatus, undoubtedly an expression of what the Black Forest philosopher called 'Western metaphysics'. Heidegger, for Crawford, is the German philosopher who tried to inflect philosophy in the direction of concreteness, of palpable substance, having realised that Western philosophy had reached a dead end, with no hope of escape.

Crawford, like Foucault, is therefore a Heideggerian seeking to find concreteness behind the Western ideological jumble. Crawford and Foucault noted, following a close reading of the writings of their Swabian master, that Locke, the emblematic figure of Anglo-Saxon thought and, consequently, of the dominant political thought in the entire Americanosphere, rejected reality in all its aspects as a mediocre collection of trivialities. Locke's position, the founding father of a liberalism that now dominates the planet, led to any contact with concrete, tangible and substantial realities being regarded as non-philosophical or even anti-philosophical, and therefore as a process that was unimportant or even fraught with perversities that should be forgotten or repressed.

Foucault, before Crawford, had emphasised the need to get rid of this oppressive conceptual apparatus, even though it was in perpetual levitation, deliberately seeking to break all contact with reality, to detach men and peoples from any resourcement in concreteness. In his early writings, which Bousquet does not cite, Foucault showed that the mechanisms of power inaugurated by the Enlightenment of the 18th century in no way constituted a movement of liberation, as Western propaganda would have us believe, but, on the contrary, a subtle movement to bring men and souls into line, designed to erect humanity, align it with rigid patterns and homogenise it. From this perspective, Foucault observed that, for the modernity of the Enlightenment, the heterogeneity that constitutes the world - the countless differences between peoples, religions, cultures, social or ethnic 'patterns' - had to disappear irretrievably. As a philosopher and ethnologist, Claude Lévi-Strauss argued in favour of maintaining all ethno-social patterns in order to save the heterogeneity of the human race, because it was precisely this heterogeneity that enabled man to make choices, to opt, if need be, for other models if his own, those of his inheritance, were to fail, weaken, no longer able to stand up to the struggle for life. Lévi-Strauss's option was therefore ethnopluralist.

Foucault, on the other hand, chose a different path in order to escape, he believed, from the grip of the mechanisms inaugurated by the Enlightenment and aimed at the total and complete homogenisation of humanity, all races, ethnic groups and cultures taken together. For Foucault, an audacious interpreter of Nietzsche's philosophy, man, as an individual, had to 'sculpt himself', to make a new sculpture of himself according to his whims and desires, by combining as many elements as possible, chosen arbitrarily to change his physical and sexual make-up, as the gender theories would later suggest in force, to the point of madness. It is this interpretation of the Nietzschean message that Bousquet, in his new neo-Rightist pamphlet, has roundly criticised. But, quite apart from this rascally audacity on the part of Foucault and all the Foucauldians who followed him, Foucault's thought is also Nietzschean and Heideggerian when it sets out to elicit a 'genealogical and archaeological' method for understanding the process of emergence of our Western civilisational framework, now rigidified.

I think that Bousquet should have taken account of several of Foucault's refusals if he was not to remain at the stage of pure pamphleteering pruritus: the Foucauldian critique of the homogenisation of the Enlightenment and of the Lockean rejection of reality as an insufficiency unworthy of the philosopher's interest (cf. Crawford), the double archaeological and genealogical method (which the French philosopher Angèle Kremer-Marietti had once highlighted in one of the first works devoted to Foucault). By ignoring these positive and fertile aspects of Foucault's thought, Bousquet runs the risk of reintroducing conceptual rigidity into the alternative metapolitical strategies he intends to deploy. Bousquet's anti-Foucaldism certainly has its reasons, but it seems to me inappropriate to oppose new rigidities to the current apparatus constituted by the dominant ideological nuisances. Foucault remains, despite his many gyrations, a master who teaches us to understand the oppressive aspects of the modernity that emerged from the Enlightenment. The bankruptcy of the political establishments inspired by the Lockian jumble is today leading the proponents of this demonetised battleground to resort to repression against all those who, to paraphrase Crawford, pretend to want to return to a concrete and substantial reality. They drop the mask that Foucault, after Nietzsche, tried to tear off. So modernity is indeed a range of oppressive devices: it can conceal this fundamental nature for as long as it holds on to a power that functions for all it's worth. When that power begins to crumble, that nature comes rushing back.

In the end, the festivism of the post-Foucauldians was no more than a thin layer of paint to give the "Lockean" establishments extra wood. In this respect, Crawford is, in the contemporary context, more relevant and comprehensible than Foucault when he explains how the supposedly liberating thoughts of the Lockeans have distanced man from the real, which is judged to be imperfect and badly arranged. This reality, by its heavy presence, handicaps reason, Locke thought, and leads men to the absurd. Here we have, in anticipation, and on an apparently reasonable and decent philosophical level, the defensive and aggressive reflex of today's establishment in the face of various so-called 'populist' reactions, rooted in the reality of everyday life. This reality and this everyday life are rebelling against an imposed and anti-realist political thinking that denies the springs of the "really existing reality", of the "reality without (imaginary) double" (Clément Rosset). Dominant political thought and the legal apparatus are Lockean," says Crawford, "insofar as the real, any concreteness, any tangibility, is again posited as imperfect, insufficient, absurd. The proponents of these arrogant postures are in denial, denial of everything. And this absolute denial will end up tipping over into repression or sinking into ridicule, or both, in a buffoonish, grimacing apotheosis. In France, the trio of Cazeneuve, Valls and Hollande, and the procession of females swirling around them, are already giving us a foretaste, if not an illustration.

Foucault had discovered that all the forms of law established since 17th century France (cf. his book entitled "Théories et institutions pénales") were repressive. They had abandoned a law, of Frankish and Germanic origin, which was genuinely libertarian and popular, and exchanged it for a legal and judicial apparatus that was violent in essence, anti-realist, hostile to the 'really existing real' that is, for example, the populace. The behaviour of certain French judges in the face of popular, realistic and accepting reactions, or in the face of writings judged incompatible with the rigid postures derived from the fundamental anti-realism of the false thinking of the 17th and 18th centuries, is symptomatic of the intrinsically repressive nature of this established set, of this false libertarianism and revolutionism now rigidified because institutionalised.

We might therefore perceive 'French Theory', and its derivative aspects of Foucault's thought (in its various successive aspects), not as a vast instrumentarium aimed at arbitrarily recreating man and society as they have never been before in history and in phylogenesis, but, on the contrary, as a panoply of tools for ridding ourselves of the burden that Heidegger referred to as failed "metaphysical constructions" that now heavily obliterate real life, the vital givens of human peoples and individualities. We need to equip ourselves with the conceptual tools to criticise and reject the oppressive and homogenising devices of Western (Lockean) modernity, which have led societies in the Americanosphere into absurdity and decline. What's more, a coherent and philosophically well-founded rejection of the apparatuses of the Enlightenment means not inventing a supposedly new and fabricated man (sculpted, as Foucault would say in what must be called his delirium...).

The anthropology of the revolt against oppressive devices that take on the mask of freedom and emancipation posits a different kind of man from the seraphimised man of the dry and atrabilious Lockeans or the man modelled according to the whimsical fantasies of the delirious Foucault of the 70s and 80s. The way forward is a return/recourse to what thinkers like Julius Evola and Frithjof Schuon called Tradition. The paths for shaping man, for lifting him out of his miserable condition, woven of dereliction, without however chasing him away from reality and the permanent frictions it imposes (Clausewitz), have already been mapped out, probably at the "axial periods" of history (Karl Jaspers). These traditional paths aim to give the best of men a solid backbone, to give them a centre (Schuon). Spiritual asceticism does exist (and does not necessarily impose pain or self-flagellation). The 'exercises' suggested by these traditions must be rediscovered, as the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk has recently recommended. In fact, Sloterdijk urges his contemporaries to rediscover the 'exercises' of yesteryear to discipline their minds and reorientate themselves in the world, in order to escape the dead ends of the false anthropology of the Enlightenment and its pitiful ideological avatars of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Gender studies and post-Foucauldian gesticulations are also dead ends and failures: they heralded our 'kali yuga', imagined by ancient Vedic India, a time of advanced decay when men and women behave like the bandarlogs in Kipling's 'Jungle Book'. A return to these traditions and exercises, under the triple patronage of Evola, Schuon and Sloterdijk, would mean putting a definitive parenthesis to the bizarre and ridiculous experiments that have led the West to its current decline, that have led Westerners to fall deeply, to become bandarlogs.

Robert Steuckers,

Brussels-City, June 2016.

(*) Bousquet's problem is that he castigates this large-format carnival from an equally carnivalesque, mini-format cenacle, where figures à la Jérôme Bosch wiggle and jiggle.

Commentaires

Enregistrer un commentaire